The word futurist is quite generative. From it we get the arts movement that so influenced science fiction for better and for worse during the Pulp Era, as discussed in the previous half of this article. However, there is another more modern usage: people and organizations in the business of predicting future trends. In this sense, science fiction is not futurist despite claims to the contrary. The physics of exactly how Chewie punches the Millennium Falcon through hyperspace is handwaved away, and thirty years after A New Hope, hyperdrive technology remains at the edges of pseudo-science. And that’s okay.

The Cave Wall

It is more accurate to say that science fiction is inspirational at its best, but more fundamentally projective; our desires, anxieties, and hopes for our many futures a shadow play on the cave walls behind a snapping fire (Horney, 1991). Even a casual reading of the two subgenres under discussion here, Afrofuturism and solarpunk, makes this clear.

Afrofuturists rewire temporal and technological spaces to reposition our experiences, centering them. We are quite done playing the fool, monster, or faceless victim. Yet hopeful, healing stories of a better near-future seem forever endangered by old wounds and new.

Solarpunk, on the other hand, recognizes the dire ecological threat of the Anthropocene, yet wishes to oppose a dystopian worldview—to speak friend and enter the 21st Century with revolution in mind for all communities. Unfortunately, it has not yet found a solid connection with the underrepresented groups it’s meant to include.

I believe that when combined, the alchemy of these two sub-genres will produce an elixir that is medicinal to Afrofuturism, lifesaving to solarpunk, and healing to all who create in or explore their shared spaces. In this, part two of my essay, I will discuss why integration is necessary and offer suggestions for how it might come about. But first, let’s dig into solarpunk…

Don’t Call it Utopia

Many of the published ecological utopian stories of the early 20th century were toxically masculine, anxiety-driven, Eurocentric, and downright lethal. In H.G. Wells’ “Men Like Gods” for example, an extraplanetary race of advanced humans, the “Utopians,” have achieved worldwide monoculture by refining extermination to Super Saiyan efficiency, murdering their way to an all-consuming perfection. As one Utopian put it, “Before [us] lies knowledge and we may take, and take, and take, as we grow. These were the good guys in Wells’ story (Alt, 2014). Though there is no direct line of succession, subsequent ecological stories were in conversation with the viability of this image of the shining city upon the hill and, by the time of Ursula K. Le Guin, some authors were pushing back hard against this Utopian mindset: antidote for the toxin, yin to counteract the damage done by the “big yang motorcycle trip” (Prettyman, 2014).

Enter the solarpunk movement.

Peter Frase, author of Four Futures: Life after Capitalism, put it best: “[These stories] demand more of us than simply embracing technology and innovation.” They require a perspective that “sees human development as…a process of becoming ever-more attached to and intimate with a panoply of nonhuman natures” (Frase, 2016).

Here is solarpunk as captured in the words of the creatives. Emphasis varies, but there are patterns: optimism, sustainability, social justice, anti-racism. This has not changed much since the term was coined around 2008. The digital solarpunk communities on Medium, Tumbler, Twitter, Facebook, and others agree on and elaborate these points of orthodoxy through conversations around the articles they post and the art they share.

Michael J. DeLuca, publisher of the journal Reckoning: Creative Writing on Environmental Justice, was the solarpunk expert on my Readercon panel “Afrofuturism and Solarpunk in Dialogue.” He is not enamored of the name “solarpunk,” because it is possible to overemphasize solar energy as an aesthetic or silver bullet alternative resource. His point is valid. Even focusing just on new sustainable energy production bottlenecks the scope of solarpunk. The dangers posed by climate change destruction deterioration tasks solarpunk narratives and art to explore and innovate with various fields of harder science to navigate the fire line between ecological recovery and collective immolation.

As author Claudie Arsenault says, “[Solarpunk should work] from existing technologies, from things we already know are possible.” This is a powerful throughline in both solarpunk and Afrofuturism. “The distillation of African [and] diasporic experience, rooted in the past but not weighed down by it, contiguous yet continually transformed” (Nelson, 2002). For example, Michael DeLuca and other creatives include indigenous community farming practices in solarpunk. Not just because these communities may have discovered years ago the answers to some of today’s ecological problems, but also because solarpunk’s narrative/manifesto (with the provocative exception of the creators behind the Hieroglyphics project) is of a future woven from the experiences of non-dominant peoples.

But all is not well in Digital Solarpunklandia.

Despite diverse admins, you have to scroll pretty deep into the membership before you count more than ten black faces in these platforms and communities. The Facebook group actually has a breakaway called “Solarpunk But With Less Racism.” And while, relative to mainstream sci-fi, people of color are overrepresented as main characters in solarpunk, the majority of authors who write them are not. It is difficult to see how this explicitly anti-racist movement can develop without direct engagement with those whose collective recent experience involves pulling themselves off the pointy end of Western utopic aspirations. The solarpunk anti-racist mission is in grave danger otherwise, and there are real-world consequences.

During my Readercon panel, author Cadwell Turnbull asked who owned the technology shaping the future. In 2013 intellectual property made up ninety percent of European exports, much of which flooded info Africa. Africa had become the next frontier for property developers and architectural consultancies running out of work in the Global North. Green lingo like “Smart-cities” or “Eco-cities” were used to sell city plans that did not take into account the actual needs of the communities and resulted in “ghost cities” that few can afford to live in: surface-level solarpunk aesthetic, but a sun-bleached shell of its true purpose (Frase, 2016) (Watson V. , 2012).

If the “solar” stands for hope, then the “punk” part of the equation is the kernel of open source programming that maintains the genre’s anti-racist, pro-social justice drive, despite the inherent pressures of the (mostly affluent, White, English-speaking) community in which it was created. For solarpunk to grow into what it truly wants to be, it needs Afrofuturism.

Social Justice as Survival Technology

The deteriorating state of our biosphere is the product of political decisions and has little to do with a missing-link technological discovery. Michael DeLuca defines solarpunk as “stories of teams of bright young people coming up with solutions to save the planet.” But these cannot just be engineers and scientists. It must include activists, the people on the frontlines of social justice.

It is often assumed that the push to save the ecosystem will come hand in hand with equality for oppressed groups, because both are part of a broad progressive platform. But compromises are made all the time.

Solarpunk: Ecological and Fantastical Stories in a Sustainable World is possibly the first ever solarpunk anthology. It was first published in Brazil in 2012 by Gerson Lodi-Riberio, and then translated to English by Fabio Fernandes and published here by World Weaver Press in 2018. Brazil has been a world leader in renewable energies for at least a decade but is anything but a model for economic and racial equality. In translator Fabio Fernandes’s words, “[the people] strive to make a living in a shattered economy in every possible way” (Lodi-Ribeiro & Fernandes, 2012, 2018).

Romeu Martins’ story “Breaking News!” slides right up to the edge of dystopia. Told as a quasi-radio drama, we witness a civilian takeover of the TranCiênca corporate greenhouse and ecological research facility. Then something goes horribly wrong and the civilians, in brutal detail, suddenly slaughter each other. We learn later this was the result of an experimental mind control gas the TranCiênca purposefully released at the facility—a weapons test (Lodi-Ribeiro & Fernandes, 2012, 2018).

Madeline Ashby’s “By the Time We Get to Arizona” is found in Hieroglyphics, an anthology of stories based on collaborations between authors and scientists engaged in “moonshot” research. Ashby’s story is about a Mexican couple trying to gain United States citizenship. They must subject themselves to deeply intrusive data mining and reality show-style 24-hour surveillance in a suburban eco-village on the southern side of the border between Mexico and Arizona. It’s run by a massive solar energy corporation to which the governments have partially outsourced border control. Things seems to be going well for the couple until they get pregnant, which if found out would scuttle their chances at citizenship (Cramer & Finn, 2014).

If solarpunk finds solutions to environmental problems that do not uplift marginalized communities, then we’re just outsourcing suffering to build a New Elysium atop dystopian favelas. And making use of indigenous peoples’ solutions without considering their needs or their narratives is colonialism in artisanal sheep skin, locally sourced. As Daniel José Older has said, what we need is “power with rather than power over.”

Kim Stanley Robinson calls social justice “survival technology” (Robinson, 2014), and it must be at least as advanced, exploratory, and revolutionary as the renewable energy research that consumes the majority of solarpunk discussion. Here again, Afrofuturism can fill a much-needed gap. Solarpunk creatives don’t need to reinvent the wheel; they need to communicate with the ones who built it the first time.

The Work of Griots

“The writers, the visionaries, those folks who are able to imagine freedom are absolutely necessary to opening up enough space for folks to imagine that there’s a possibility to exist outside of the current system. When we take a small step outside that, we are able to break that indoctrination and see that this is not the only way, and in fact there are as many ways to exist as we can imagine.” —Walidah Imarisha

Michael DeLuca has been actively looking for Afrosolarpunk stories, and he is certainly not the only one. Yet here we are. There could be many reasons why there are so few of us engaged in solarpunk. It is likely most Afrofuturist creatives haven’t heard about it or haven’t been invited to join in large enough numbers for it to be a thing. That we can fix. But there may be deeper reasons.

I think Walidah Imarisha says it beautifully in the quote above, so I will only add this: that Afrofuturist stories are born from survivors of dystopia. Dystopia forces painful masks upon us. Seeing the world through suffering eyes while trying to imagine the future can trigger anxiety before triggering hope. But Sarena Ulibarri, editor of Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers, reminds us there is much more written about solarpunk than there are solarpunk stories being written. That means its identity is still being formed and there is room to grow. Despite its flaws, solarpunk aggregates mind-bending idea after mind-bending idea after mind-bending idea, each meant to shatter dystopia with the force of a green tree shoot cracking concrete from the ground up.

The act of creating solarpunk stories can be healing. What you create can be a different mask, one of your own choosing; one made of hope, made of power, and connected to a tradition of griots shaping the future with their dreams. I can wear the mask. You can wear the mask. Anyone can wear the mask. And we won’t be the only ones.

That We Can Fix…

The communities engaged with the solarpunk movement need to integrate. The solutions I propose are straightforward: coordinated action, organization, and direct outreach to Afrofuturists. What follows is a short reference guide and suggestions for specific projects. As you will see, I’m naming names in the interest of connection, outreach, and inspiration:

Let’s start with the basics: Ivy Spadille, Stefani Cox, Juliana Goodman, Takim Williams, Milton J Davis, Nisi Shawl, Tananarive Due, Marlon James, Nicky Drayden, Jennifer Marie Brissett, Phenderson Djéli Clark, Zig Zag Claybourne, Rob Cameron (that’s me!), Danny Lore, Victor Lavalle, Cadwell Turnbell, Terence Taylor, Erin Roberts, Maylon Edwards, Sheree Renée Thomas, Essowe Tchalim, Zin E. Rocklyn, Victor Lavalle, and Kiini Ibura Salaam. If you are looking for excellent black speculative arts writers (and an artist: John Ira Jennings) to ask for solarpunk stories, here is a starter list.

Throughout this essay, I have liberally hyperlinked to that I think would be excellent resources such as this post about Black women engaged in environmental justice or this book of essays on the Black Anarchists. But as with the authors list above, there are more, many more.

Urban Playgrounds

The solarpunk movement’s primary focus is wherever people already are; therefore the urban setting is as vital to solarpunk as it is to Black speculative fiction. The city is a fun place to play. For example: Annalee Newitz is the author of “Two Scenarios for the Future of Solar Energy,” a conte philosophic on biomimetic cities. Nigerian born architect Olalekan Jeyifous designed architecture for African cities that centralized the needs and knowledge of the poor rather than sweeping them aside. A dialogue between these two creatives would generate whole worlds of urban-focused moonshot stories. What if formally incarcerated black urban farmers wrested control of legal pot industries back from Monsanto in a Chicago with buildings that sequestered CO2? If this was a show, I would binge-watch it.

Collaborating Editors and Publications

Moving on to the Solarpunk editors of note: Ed Finn, Kathryn Crammer, Gerson Lodi-Ribeiro, Phoebe Wagner, Brontë Christopher Wieland, Sarena Ulibarri, and Michael DeLuca.

Below are editors with a long history publishing Black speculative artists and underrepresented voices, and who would be excellent collaborators. All the editors named here are professionals with deep connections with the communities solarpunk is trying to reach:

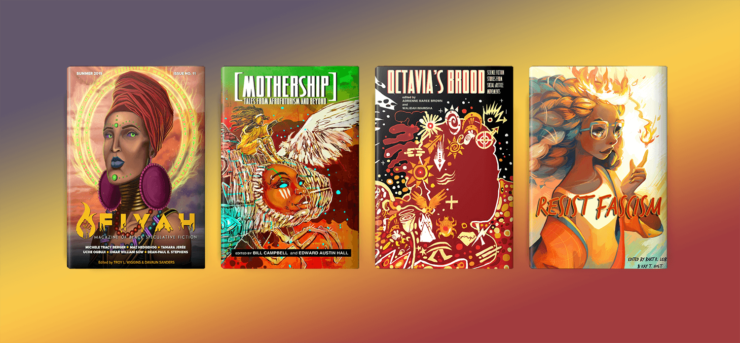

- Octavia’s Brood was published by Walidah Imarisha and Adrienne Maree Brown with AK Press. It was groundbreaking. Social activists and speculative fiction writers came together to write relevant stories. What we need now is Octavia’s Seed. Taking a page from the Hieroglyphs project and Ed Finn’s Arizona Center for Science and the Imagination (a good resource for experts in solarpunk-friendly scientific fields), authors would collaborate with social activists and scientists/engineers.

- Bill Campbell runs Rosarium Publishing and is responsible for Mothership, Stories for Chip (edited by Nisi Shawl) and many others.

- Crossed Genres, while not specifically Afrofuturist, brought us Resist Fascism (edited by Bart R. Leib and Kay T. Holt), Long Hidden edited by Rose Fox and Daniel José Older), and Hidden Youth (edited by Mikki Kendall and Chesya Burke). It is Crossed Genres’ mission to “give a voice to people often ignored or marginalized in SFF.” Of particular interest are their publications on skilled laborers and people marginalized throughout history.

- World Fantasy Award-winning FIYAH Literary Magazine publishes amazing speculative fiction from Black authors around a theme. I’d suggest a collaboration with them that instead engages a specific solarpunk-oriented non-fiction resource. That resource might be a text or based on a digital symposium with specialists conducted via Facebook, Livestream, etc.

Digital Communities in Conversation: To the Admins of the Facebook Solarpunk

Digital symposiums and direct outreach is also prescribed for the various communities active on social media. The Facebook Solarpunk community has about 3,000 members. Black Geeks Society and Nerds of Color has 2,800. The State of Black Science Fiction Group has 17,000. PLANETEJOBN: The Extraordinary Journey of a Black Nerd Group has over 250,000. Many of these members are creatives as well as lovers of speculative fiction (including Fabio Fernandes). Milton Davis, Jermaine Hall, Sheaquann Datts and the other admins are open-minded and adventurous. Collaborating on a shared project could be amazingly productive and would most likely filter out to conversations at the various science fiction conventions around the country, thus reaching even more people.

Upper Rubber Boot Press has a regular Twitter #Solarpunk Chat run by Deb Merriam that you can use as a model, and they would even be open to your group guiding a monthly conversation.

If I’ve overlooked or forgotten any creatives, writer, editors, or resources that should be a part of this conversation, please feel free to bring them up in the comments!

Bibliography

Alt, C. (2014). Extinction, Extermination, and the Ecological Optimism of H.G. Wells. In K. S. Gerry Canavan.

Cramer, K., & Finn, E. (2014). Hieroglyph: Stories & Visions for a Better Future. HarperCollins.

Frase, P. (2016). Four Futures: Visions of the World After Capitalism. Verso Books.

Horney, K. (1991). Neurosis and Human Growth. New York: Norton Paperback.

Lodi-Ribeiro, G., & Fernandes, F. (2012, 2018). Solarpunk: Ecological and Fantastical Stories in a Sustainable World. World Weaver PRess.

Nelson, A. (2002). Introductions. Social Text 20.2 Summer, 1-14.

Otto, E. C. (2014). “The Rain Feels New”: Ectopian Strategies in the Short FIctionof Paulo Bacigalupi. In E. b. Robinson, Green Planets: Ecology and Science Fiction (p. 179).

Prettyman, G. (2014). Daoism, Ecology, and World Reduction in Le Guin’s Utopian Fictions. In E. b. Robinson, Green Planets: Ecology and Science Fiction (p. 56).

Robinson, G. C. (2014). Afterward: “Still, I’m Relunctant to Call This Pessimism”. In E. b. Robinson, Green Planets: Ecology and Science Fiction (p. 243).

Santesso, A. (2014). Fascism and Science Fiction . Science Fiction Studies, 136-162.

Ulibarri, S. (2017). Solarpunk: Ecological and Fantastical Stories in a Sustainable World. In E. b. Lodi-Ribeiro. Albuquerque, New Mexico: World Weaver Press.

Ulibarri, S. (2018). Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers. Albuquerque, New Mexico: World Weaver Press.

Vandermeer, A. a. (2016). The Big Book of Science Fiction. Vintage Books.

Wagner, P., & Wieland, B. C. (2017). Sunvault: Stories of Solarpunk and Eco-Speculation. Nashville Tennessee: Upper Rubber Boot.

Watson, T. (2017). The Boston Hearth Project. In e. b. Wieland, Sunvault: Stories of Solarpunk and Eco-Speculation. Nahville, Tennessee.

Watson, V. (2012). African Urban Fantasies: Dreams or Nightmares. University of Cape Town: School of Architecture, Planning and Geomatics,.

Wieland, E. b. (2017). Sunvault: Stories of Solarpunk and Eco-Speculation. Nashville Tennessee: Upper Rubber Boot.

Rob Cameron (though not his real name, it is written on all of his bylines) writes strange stories, one of which, “Squeeze” can be found in Mike Allen’s anthology Clockwork Phoenix 5 (Mythic Delirium, 2016). His story “Tatterdemallion at the End of the Universe” is curriculum material for the Carterhaugh School of Folklore and the Fantastic. He is a linguist and an ENL teacher in Brooklyn. When not getting paid, he is managing editor and a producer for the Kaleidocast.nyc, a lead organizer for the Brooklyn Speculative Fiction Writers, sometimes curator for the New York Review of Science Fiction’s Reading Series, the Surreal Symphony of Zak Zyz, and also does speculative fiction programming at the Center for Fiction and BSFW’s Expert Series. He is also a pie addict with neither regrets nor inclinations towards rehab. Find him at: http://www.rob-cameron.com/